The Traditional Birth Attendants that we interviewed. They had just come from a training workshop.

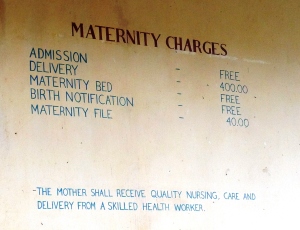

To get a better understanding of the situation at the hospital, we interviewed the doctor, nurses, mothers and traditional birth attendants (TBAs). From interviewing the nurses, we learned that of the 49 beds available in the hospital, 8 are in the maternity ward and 6 in the pediatric ward. The wards are severely overcrowded and we witnessed cases were two mothers were sharing a single bed. A delivery costs about $5 if there are no complications. This may seem as a small amount for you and I, but keep in mind that these mothers are in one of the poorest provinces in Kenya with poverty levels of over 70%. The women are encouraged to give birth at the hospital because of a major campaign going on to address the huge HIV/AIDS epidemic in the region. Under the Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission (PMTCT) campaign, pregnant mothers have to undergo mandatory testing so that the right course of action can be taken if they are found to be HIV positive.

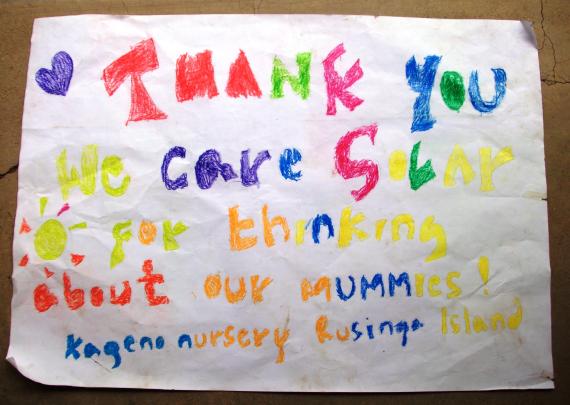

MCH Notice board

At the Maternal and Child Health center, mothers are encouraged to come for 4 pre-natal visits. Most mothers have been observed to make 3 out of the 4 visits, usually in their 2nd and 3rd trimesters. A majority immunize their babies even if they had a home delivery. Less than 20% are reluctant to immunize their babies and mostly due to religious regions. Nonetheless, those who do, return to the village and spread the word. When all is said and done,70% of mothers are still giving birth at home. The reason for this tremendous gap is cause for great concern.Clearly the community has lost faith in their hospital facilities. This is one of the reasons that attributes to such a vast majority delivering at home.

There are several other reasons why mothers opt for home births. For one, they are afraid of being tested and knowing their HIV status. Secondly, there have been cases of mothers being abused, both physically and emotionally, by the nurses. The nurses are quick to defend themselves by pointing out that they have received cases of women having being abused by these traditional birth attendants. They add that the TBAs give a false impression of being comforting as they do not disclose to the mother when complications arise. In addition, mothers say that they also enjoy the support and privacy of delivering in their own homes. Transportation is another major hindrance to women delivering in hospitals. Pregnant women often have to walk for miles from their homes to the main road and then wait for an unknown amount of time for a public transportation vehicle. Others are brought to the hospitals in wheel barrows or on the back of a bicycle. It all just seems like way too many hurdles to get over to get to a hospital where adequate obstetric care is not a guarantee.There is also a barter payment system accepted by the TBAs in the form of things like chicken or harvest if the woman does not have actually money to pay for the services. They can also pay the TBAs in installments. The nurses argue that despite these reasons that make home births seem like the better option, of the average 4 deliveries they attend to in 24 hours, at least one of them is a complication from a home birth gone bad. Most of these complications are preventable and are mostly due to long labors and extensive tearing.

Interviewing a mother in the maternity ward. Observe how close the beds are

The strange thing is that of those women we interviewed in the labor ward, although satisfied with the quality of service they had received, they seemed to be least concerned about the space issue; it’s as if they have accepted the situation and probably think that overcrowding in wards is the norm. Only with a leading question, on what they thought about the overcrowding in the wards, did it occur to them that it might be a problem.

When we finally got to talk to the TBAs, they were not very free to talk to us which we guessed was probably because the head nurse was in the group, and secondly, as we learned later was because their trainer was also in their midst and they thought they would get in trouble if they admitted to still delivering babies. Later on, as we left the compound, we ran into one of them who was very forthcoming with information. TBAs are faced with a conflict of interest in their operations. Initially they had been given training and some equipment, rubber gloves etc, to help them in their operations, so that they could go to the village and be trained midwives. Now because of the PMTCT campaign, they were told NOT to deliver babies as they do not have a way to test these mothers and know if they are HIV positive or not. Nonetheless the women in the village still run to them when they are in labor and ask for their services; often when it is too late for the mother to be taken to hospital as the baby will be coming any minute. The TBAs complained of not getting paid for their services. If the mothers at home are willing to pay them, then that is clearly a great incentive for them to still offer their midwife services. They also lamented that the equipment that they had been given had experienced, as one them phrased it ever so eloquently, “wear and tear” and had not been replaced since.

These incubators are squeezed in on one corner of the maternity ward one of which was out of commission.Often they have more than one baby in an incubator. During power outages they use the "kangaroo method" where a mother makes a pouch for her little one

At the end of each interview, we would ask each person we interviewed what changes they would make in the hospital if finances, labor and time were not an issue. It came down to these three major things – Space, Equipment and Staff. The nurses are clearly overworked. They don’t have a very conducive working environment which explains why they would be short with the patients. Religion, culture and education play a major role in whether or not the mothers will be delivering at home or at the hospital. A majority of the mothers in the ward were first time mothers and very young – late teens and early twenties. We found out that even when it comes to birth control issues, they still had to seek permission from their spouses. A lot of these young mothers when we talked to them had no say in how many children they would like to have. They could not even answer that question in a hypothetical sense. As one of them put it, “it is not my decision”.

Electricity was the least of their worries although they emphasized that they experience major power outages during the rainy season. The national grid is extremely unreliable during this time and they have to depend entirely on the generator. This proves to be quite expensive for the hospital and when there are no finances to buy fuel they have to use kerosene lamps. The long rains are experienced between March and May, the short rains October to December. This being the month of June, we were not going to be able to witness the effect of these rains. It was quite the conundrum trying to figure out how the project should progress. Installing this pilot suitcase here would mean that it would be stored away and used purely for emergency purposes. It also meant that we would have to wait till October to get any feedback data. Then again, taking the project away from the community after they had been extremely receptive would mean that we were just another bunch of foreigners collecting data with empty promises. The day ended with a lot for both Jenny and I to think about. As we walked back to our hotel recollecting the days events, we remembered the smiles on these mothers faces and that was enough to remind us of the reason we were out here enduring the scorching sun, mosquitoes, and dust.